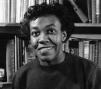

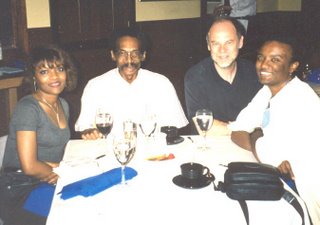

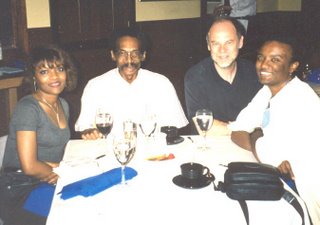

For a couple of years, Lorenzo Thomas and I conspired to be in Boulder, Colorado, at the same time when we could. This began when my wife, Anna Everett, was teaching in Film Studies at the University of Colorado. During our stay there, we of course took advantage of the programming at Naropa, which included Lorenzo nearly every year. From that first summer, we tried to arrange our visits for the Fourth of July so that we could cap the evening with fireworks over Boulder. This photograph shows one of our last visits. Here we're at dinner, joined by Harryette Mullen, who was also visiting Naropa that season. It really was a poetry family affair. These were great poets and great company.

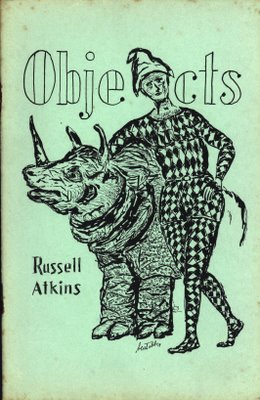

I had been reading Lorenzo Thomas's poetry for many years before I first met him. His chapbooks and selected volumes were among the small number of small press titles that would show up in book stores in D.C. in those days, and his was the kind of work that made you seek out more. It wasn't until the latter part of the 1980s that I met him, though; we were introduced to one another by Charles Bernstein in a hotel lobby during one of the MLA's visits to D.C. - People often wonder at my love of academic conferences, but meetings like that one are among the reasons I try to stay active in these professional associations. Over the years, conferences were where Lorenzo and I visited with one another. We also increasingly found ourselves working together on conference projects. There were so many occasions when we spoke together, or when one of us was the respondent to the other, that we were becoming a sort of critical/poetic tag team at these events. Lorenzo was somebody you would always learn something from, and he was also among the most generous people I've ever known. Much of my work on poetry and music was helped along by Lorenzo's willingness to share his collection of recordings with me. Typically this would happen when, over drinks (as in the photo above) I would ask Lorenzo if, say, he'd ever come across an LP titled NEW JAZZ POETS. He would muse a moment, then invariably came the same answer: "I think that may be in the closet in New York. I'll ask my brother to dig it out for us." Lorenzo's brother, Cecilio, a person every bit as kind and generous as Lorenzo, was the artist whose work appears in so many of Lorenzo's publications. About a month later, I would get a cassette tape in the mail.

I was able to help a bit in Lorenzo's work as well. On several occasions I was a"blinded" peer reviewer for Lorenzo's critical works. A particular pleasure was being able to do that work with the manuscript of EXTRAORDINARY MEASURES, a book increasingly cited by other scholars.

When Lorenzo died this past July 4th, I had just read the manuscript for a book about music that he had submitted to the University of Michigan Press. I've been in discussions with the press since Lorenzo's passing, and I am happy to report that they are willing to go forward with the project. In the coming months, I'll be working to get the manuscript into final shape for publication. Barry Maxwell is also working on a collection of Lorenzo's essays and talks.

A few years back, Barry organized a panel on Lorenzo's work at the American Studies Association meeting in Houston, where we were joined by Kalamu ya Salaam and Maria Damon. We had a great dinner afterwards with Lorenzo and Karen, and Roberta Hill. Wish to god I'd had my camera along that time. Jim Smethurst has organized a panel in Lorenzo's memory that has just been approved for the next American Studies meeting at Oakland in the Fall.

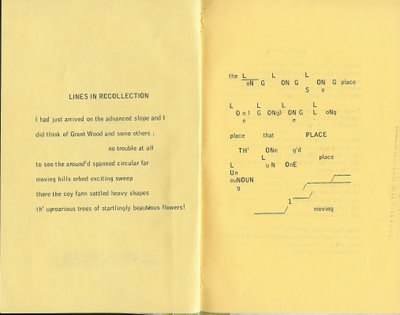

It is as a poet, though, that Lorenzo Thomas has the greatest claim on our attentions. The last serious time I spent with Lorenzo was at the conference held at Miami Univeristy in Ohio that has since been memorialized in the anthology RAINBOW DARKNESS, edited by Keith Tuma. Lorenzo read his poetry and delivered a keynote address, included in the anthology. You can find information about the book at:

http://www.orgs.muohio.edu/mupress.

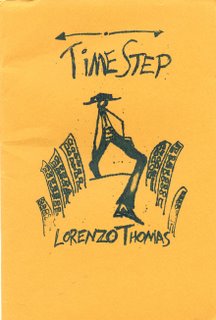

Lorenzo's last pulished full colletion of poetry was DANCING ON MAIN STREET, which includes the chapbook shown here, TIME STEP, and was published by Coffee House Press. John Ashbery had this to say about Lorenzo's final book:

"Lorenzo Thomas's poems have a graceful New York School nonchalance that can swiftly become a hard and cutting edge when he writes of the African American experience, especially in his adopted home of Texas. 'This useless clairvoyance/is embarrassing,' he confides. Yet Thomas's brand of clairvoyance is not only useful, but beautiful."— The book is still available, and you can find information bout it at: http://www.coffeehousepress.org/dancingonmainstreet.aspIn the future, I hope to put up a Lorenzo Thomas web site. For now, here is some of his work.

DOWNTOWN BOOM

There are no gospel singers

Anymore

On the corners

They held down for Jesus

Valets park cars

At restaurants for fancy people

On expense accts or dates

So many times

People come up to me

And say, Billy

Hey wait a minute

You not Billy!

You can see the new ballpark

Just past the Courthouse

But which way is redemption?

-----------------------------------------------

AILERONS & ELEVATORS

Autumnal Equinox 2002

The backward see

The wise don't say a word

Three dreams, one foolish

And two meaningless

Are haunting me, disturbing me

One says

A golden road was plotted out for you

In dreams, of course

But that's not where you are

When you awaken

The danger is seeing the world

as two extremes

The afternoons of rushing home to see her

Balanced against

turning the corner

Hoping that her car will not be there

Daydreams are better

Nice –

watching the planes come in

On the last day of summer

Airport peaceful

Passengers are few

On flights answering demand

more than desire

Their stress has been at home

Or will come later

They deplane calmly

When the Wright boys

and their friend Paul Laurence Dunbar

Finished high school in 1890

Their neighbors knew

That they'd go high up in this world

Paul as an elevator boy in downtown Dayton

Orville and Wilbur

Going swimming in thin air

Unfortunately,

They'd never heard of Richard Gallup

David or Romare Bearden, either

Such are the baffling deficits that time imposes

They never dreamed

Someone would use an airplane

To drop bombs made of oilfield dynamite

and set Greenwood aflame

Andrew Smitherman fleeing in 1921

from Tulsa to New York

To the edge of America

What is this shadow

Cast across the coming season?

In the still watches of the Negro night,

Fear rising like mist off a bayou,

The danger in the world

Is seeing it as two extremes

Is this full moon so indiscriminate

That even liars prosper

if they have launched

Their web with the new moon?

This autumn equinox

A harvest of deceit

Leaves the ground rugged.

The harvest done, the fields outside the city

flat and sere

A single egret stands in the parking lot at the Post Office

Poised and confused

The world automatically recoils

Into itself

Are you ready for football?

For serious business

Are you ready for war?

People throughout all history

Have lived in ashen cities

or died in them

Marcel Duchamp was joking

Wasn't he, as always when he said

Dust-covered glass

Might offer auguries

Of our predicament

O mirror, mirror

How have my people been distracted so

They don't care any longer who they are?

How so misled that they believe

Punishment does not apply

To crimes committed in their name?

Must war morph from Nintendo game to spectacle

To get attention?

If all are suspect

Could my own duplicities

Be causing this –

The way we're all responsible

For air pollution

(if you keep breathing

If you believe in magic, yes

And that same magic, yes

Could stop the rush to madness, too

There are still

scraps of summer laughter

On the street

There's still some music from two backyards away

The Funkadelics and Jay-Z resist denial

But here's

The truth:

You have the right to keep your mouth shut

Trust me,

Across the room

A person looking like a crazy version

Of somebody you once knew

Might be our Savior

One who can draw fire

Out of ashes

At least a lover, maybe

The one to take you up a little higher

Or let you down easy.

But don't look this way,

It isn't me

New York City

22 September 2002